Between August 1 and August 5, 1945, the Washington Senators played five consecutive double headers. In a normal season, a scheduling burden of that magnitude wouldn’t have mattered much to the lowly Senators. But in 1945, the “first in love, first in war, and last in the American League” Senators were in a neck-and-neck pennant race with the Detroit Tigers.

Between August 1 and August 5, 1945, the Washington Senators played five consecutive double headers. In a normal season, a scheduling burden of that magnitude wouldn’t have mattered much to the lowly Senators. But in 1945, the “first in love, first in war, and last in the American League” Senators were in a neck-and-neck pennant race with the Detroit Tigers.

The Senators won nine of the 10 double header games, losing the August 4 night cap 15-4 to the Boston Red Sox. Motivated by the lopsided score, and unwilling to stretch his exhausted pitching staff further, Senators’ manger Ossie Bluege summoned his lefty Lieutenant Bert Shepard to the mound. In his Baseball in Wartime account of Shepard’s heroism, Gary Bedingfield wrote that on his 34th European Theater mission and while his P-38J Lightening was bombing an airfield near Ludwigslust, east of Hamburg, Shepard’s plane was hit by enemy flak. The shells blew Shepard’s foot off and tore through his right leg. Shepard: “I could feel my foot coming loose at the boot.” The 55th Fighter Group’s pilot’s plane hit the ground at an estimated 380 mph.

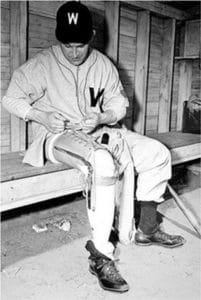

Angry German farmers rushed out of their homes, wielding pitchforks, determined to kill Shepard, the American enemy. Luckily for Shepard, First Lieutenant Ladislaus Loidl, a physician in the German Luftwaffe, saw the wreckage’s smoke, and hurried to the site in time to hold off the incensed farmers. Loidl drove the critically injured Shepard to a hospital, but the “terror flyer” wasn’t allowed admittance. Eventually another hospital accepted patient Shepard, and his leg was amputated 11” below his knee. After recuperating, Shepard spent the next eight months in POW camps where a Canadian medic and fellow prisoner made Shepard a crude artificial leg from scrap iron, wood and rivets.

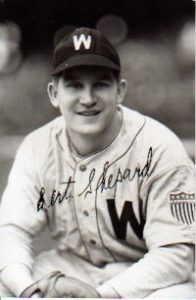

Slowly, Shepard, who as a youth moved from Indiana to California to play semi-pro baseball, began tossing the bulb around to get back a baseball’s feel. In California, Shepard’s skills were good enough to land contracts first with the Chicago White Sox and then the St. Louis Cardinals. His goal before and after his life-threatening WWII injuries was to pitch major league baseball.

A prisoner exchange returned Shepard to the U.S., and he was helped along the way to achieving his lifelong dream. At Walter Reed Hospital, Shepard met with Under Secretary of War Robert Patterson who asked about his future plans. Without hesitation, Shepard replied “to play baseball.” A skeptical but impressed Patterson contacted his friend and Senators’ owner Clark Griffith who agreed to give Shepard, now fitted with a new prothesis, a look.

As Shepard recalled, “Mr. Griffith did it out of sympathy more than anything.” But pitching in exhibition games, Shepard impressed – “got ‘em out each time,” he said. On the strength of his outstanding spring training, the Senators offered Shepard a contract with the promise that once he mastered his control, he’d be given a roster spot.

As Shepard recalled, “Mr. Griffith did it out of sympathy more than anything.” But pitching in exhibition games, Shepard impressed – “got ‘em out each time,” he said. On the strength of his outstanding spring training, the Senators offered Shepard a contract with the promise that once he mastered his control, he’d be given a roster spot.

On August 4, Shepard’s big moment arrived. With the Senators getting hammered in game two 14-2 in the fourth inning and with the bases loaded, manager Bluege signaled for Shepard who promptly struck out George Metkovich for the last out. The 13,000 assembled fans, who had followed Shepard’s progress through the nonstop media coverage of the war hero’s progress, rose to their feet to applaud. Over the next five innings, Shepard surrendered only one run on three hits, and fielded his position flawlessly.

In a perfect world, Shepard’s saga would have continued to include his promotion to the starting rotation where he would have helped carry the Senators past the Tigers to win the AL pennant, and then defeat the Chicago Cubs in the October Classic. But the world is imperfect, and 5-1/3 innings with a 1.69 ERA were Shepard’s career MLB totals.

Bluege, hoping to eke out the AL flag from the Tigers, decided to finish the year with his established starters. In 1946, players returned from active WWII duty; Shepard didn’t make the team, but was offered a coaching job. Bored, Shepard asked to be sent to the minors where he pitched for several years at Chattanooga, Waterbury and Modesto. Along his minor league journey, Shepard returned to Walter Reed to have more of his leg amputated.

April is Limb Loss and Limb Difference Awareness month, and the Amputee Coalition is an organization that would celebrate Shepard’s rewarding life that included the Distinguished Flying Cross and Air Metal awards. Before he died in 2008 at age 87, Shepard worked as a Hughes Aircraft safety engineer and an IBM typewriter salesman, played in golf tournaments with his buddy New York Yankee shortstop Phil Rizzuto, and walked 18-hole golf courses. He flew his own plane to visit amputees across the nation. Part of Shepard’s visits included encouraging demonstrations like effortlessly running the 60-yard dash and dribbling a basketball. In his later years, Shepard advocated for amputee workers’ rights and designed an artificial ankle that allowed those with severe leg injuries like his more mobility.

Shepard’s remarkable story of perseverance and achievement has a heart-warming footnote. For years, Shepard wondered about the German physician who saved his life in Germany, “Who carried me from the wreck? Who saved my life?” In May 1993, a third party arranged a meeting between Dr. Loidl and Shepard. After they met, an emotionally overwhelmed Shepard said: “I prayed for this. And after half a century, my dream has incredibly come true.”

Joe Guzzardi is a Society for American Baseball Research and Internet Baseball Writers Association member. Contact him at guzzjoe@yahoo.com.